Growing a Policy Implementation Identity

Exploring the causes and solutions to the gap between policy in writing and policy in practice

When I began writing this substack, I had a mental map of the kinds of topics I would write about —re-hashing topics I had already published in academic journals, emerging findings from current research, analyses of proposed or recently passed legislation—but then I got a little off-track in the substack woods, following the branching trails of references that turned into rabbit holes. It was glorious. And with nearly every substack post I read, I would think “I should write about this idea and how it relates to x”. But instead I would keep following the trail and never sit down and write.

Being only a year out of my PhD program, it feels very similar to the “I just need to read more” trap of dissertation writing that is really avoidance and procrastination and fear of putting your own ideas on paper. Yet, I also know that writing is how I sythesize ideas and that was the whole point of creating this space—primarily for my own benefit, but with accountability from hypothetical readers to maintain it.

Growing A Policy Implementation Identity

The major ideas I’ve been wrestling with lately cover the topics of policymaking and policy implementation. In fact, as a bit of an academic “mutt”, it is only recently that I have come to refer to myself as a policy implementation scholar—a title that solidified while attending a panel on policy implementation at the Public Management Research Conference recently. One of the driving questions of the panel seemed to be why policy implementation research and scholars were so scattered and how to better coalesce these ideas and people into a more coherent stream and intellectual agenda.

Substack (and other similar platforms) seems to be where that agenda and conversation is coalescing and, for me, the entry point was Jennifer Pahlka’s book Recoding America. Actually, it was an Ezra Klein interview with

from June of last year entitled “The Book I Wish Every Policymaker Would Read”. Because I am interested in natural resource issues, this led me to another episode on implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act in which Ezra talks with Robinson Meyer, founding executive editor of Heatmap News.The throughline that connects Pahlka’s book, Ezra Klein’s conversations and my work is the observed disconnect between policy in writing (read: legislation) and policy in practice (read: policy implementation) and curiousity about its causes and solutions. For Pahlka, who labeled this the “implementation gap”, the issues revolve around why it is so hard for governments to implement tech. For Ezra the questions are about why the good intentions of liberals have led to many of our biggest problems- lack of affordable housing, the snails pace of the energy transition. For me, the questions focus on why policy interventions and innovations intended to reshape the Forest Service to match the public values and ecological threats of the 21st century have largely failed.

The Causes of the Implementation Gap: Academia

To explore these questions, we have to look at what links policy with outcomes: the “black box” that is implementation. Greg Jordan-Detamore argues that one cause for the disconnect is the way we train future public sector workers. He argues for getting rid of the divide between public policy schools and public administration schools and fashioning them to be more like MBA programs in which strategy and implementation are taught together. Emily Tavoulareas and others argue that we need a “common core” curriculum across the various iterations of public policy and public administration degrees:

What students need to understand is (1) the entanglements between technology and public policy, (2) a basic understanding of what a digital product is and how they are designed / delivered. What can policy schools do?

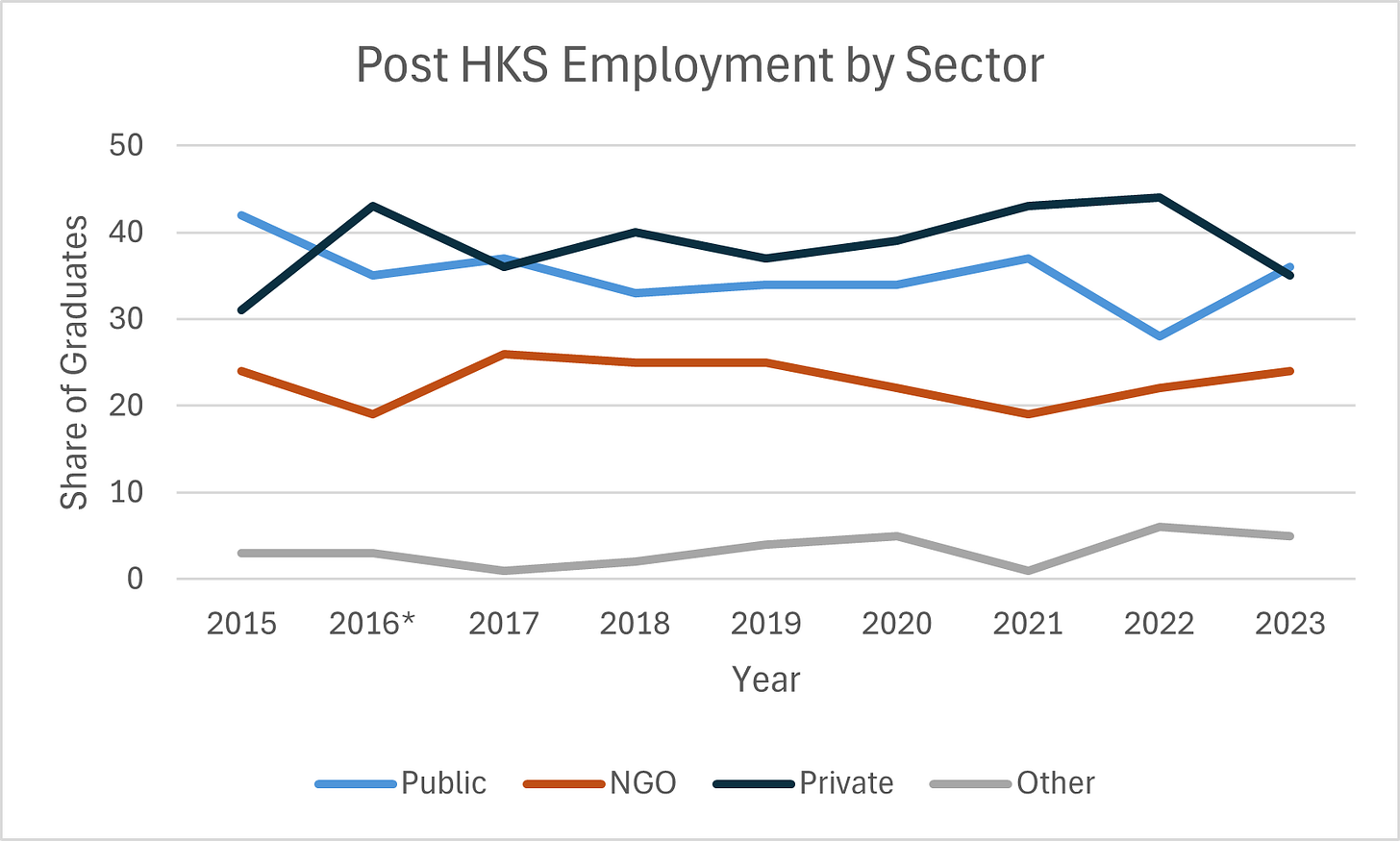

Yet, as these stats from the Harvard Kennedy School reveal, the share of graduates entering public sector employment is less than half and has been slowly declining. Does this mean they are wrong? Not at all. But, I think we need to go further and think beyond the confines of academic schools and colleges.

First, public policy and administration is civic education. This civic education was once taught in public schools. In my very small middle school in rural Idaho, we had one class that covered civics through the lens of our state: we learned the names and locations of all Idaho counties, we learned the state bird and tree, and we presumably we learned about Idaho government (although I can’t recall the latter point). I attended a webinar with the Urban Institute on planning and zoning in which the speaker made this point by showing a picture of a 3rd grade? textbook from the 1950s explaining what a county is and what it is responsible for. I doubt that many students are getting this lesson today. Thus, public policy and administration, as a form of civic education, should be included in core general education curriculum.

Second, in my college, which is a college of natural resources, we have a masters of natural resources program that primarily serves mid-career public servants working for land management agencies. Most of these students probably received a bachelor’s degree in some specialized area of natural resource management like fisheries, hydrology, forestry, etc. and most have probably never taken a course in public policy or administration even though that is what they do every day. They are policymakers implementing policy and making policy implementation decisions every day. One of the reasons that they do not enroll in MPA programs or take PA/PP courses is that they identify as specialists—foresters, recreation managers, biologists—first, and public servants second, if at all. Or, they got a business degree and became contracting officers implementing public procurement policies, but through a business lens. In fact, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) that determines the qualification for federal jobs by series states that to become a contracting officer, you must have a degree in business, law or economics. Taken together, these phenomena help to explain why, for example, federal policies aimed at social goals like procurement preferences for local contractors in forest-dependent communities do not get implemented—because contracting officers view public procurement like a private business instead of a vehicle for creating or pursuing public values.

To adapt Tavoulareas’ propositions, we need to train future land managers (or other specialists) on 1) the entanglements between science, policy and public values and 2) what a public value is and how to design for/deliver it.

The Causes of the Implementation Gap: Processes vs Outcomes

One of the reason’s I appreciate Pahlka’s book Recoding America so much is that she lays out the problems government agencies face in implementation in a way that is understandable and accessible. One of the challenges she describes is the orientation towards accountability to process rather than outcome. I have observed and experienced this in both my work and personal life, but had not been able to communicate it and it’s implications as clearly as Pahlka does.

We have all experienced the effects of accountability to process in our personal lives. I most recently encountered it trying to get a building permit from the city where I live in order to build a garage and ADU for my aging mother in law. We are not 15 months and 4 revisions into this endeavor and still do not have an approved permit. One of the reasons, in my view, that this has taken so long is accountability mechanisms that reward adherence to process rather than outcomes.

In my work studying policy implementation within the Forest Service, I have also seen how it handicaps the ability of an agency to monitor its outcomes by tailoring the collection of data points to the information required for upward reporting. That is, the agency collects information required by Congress, not what would be useful to support decisionmaking. In my last job, I spent 10 years tactfully pointing out the ways in which the Forest Service’s right hand didn’t know what its left hand was doing and producing decision support tools (mostly reports) to fill data gaps and draw connections between their fractured administrative data systems and data collected by the research branch of the same agency. So, while many point to the problems of outsourcing technology development, sometimes you need an outsider (like Pahlka and Code for America) to see the bigger picture.

Accountability structures inform incentives, rewards and sanctions. Accountability structures also influence risk tolerance and opportunities for adaptation and learning. There are many examples of public managers hiding behind process and procedures in order to reduce their risk of sanctions. AND YET, in my work studying the Forest Service, there are also many examples of employees and managers working creatively around the edges of process and procedure, taking risks to engage the public in meaningful ways even if it opens them up to critique or litigation. My dissertation examined the substance and effect of these “institution builders” and “change makers” and I think we also need more of these stories to be told as part of the policy implementation intellectual agenda.

Up Next: Solutions—Tackling the connections between regulatory reform, administrative burdens and public participation (and maybe Chevron deference)

Nice post, and thanks for the mention!

And I agree with you that another key issue is that people who are not seeking degrees that specifically focus on this stuff often get little or no instruction in it at all—despite being such an important topic not only for anyone going into government but for all citizens in general.